$20 Feint

Written by Chris Robey

I flunked AP Econ in high school but still thought, somehow, that it made perfect sense to enroll in a free online microeconomics course over ten years later. All the rabble in the news about inflation had me both fascinated and bewildered, and I wanted to make a little sense of it.

The lecturer was unabashedly geeky about his subject, bless his heart, and did his damnedest to keep the course material interesting. Well, bless my heart too, it wasn’t long before I was snoozing through every lecture.

I didn’t finish the course. Even so, two concepts have stuck with me: sunk costs—wealth you’ve spent and can never get back—and opportunity costs—wealth you forgo in choosing one thing over another. The difference between the two didn’t really strike me until months after I’d abandoned the course, however, while I was getting rid of some lightly used Muay Thai gear.

Practicing Muay Thai was a formative part of my transition from teenager to young adult. Though I’m stronger now, in certain ways, I don’t think I’ve ever had a better anaerobic threshold or VO2 max than I did as a kickboxer, even after taking up training for half marathons instead. Once, when I was eighteen and needed to get a chest x-ray done, the technician remarked on the size of my lungs with genuine astonishment.

There were physical benefits, obviously, but the training meant so much more to me than just a way of keeping fit. I befriended people from all walks of life, many of them older yet who never talked down to me and showed genuine respect, which I readily reciprocated. Sparring taught me how to focus intently on another person’s body language, anticipate their movements, and respond in kind; it’s the closest I’ve come to understanding how dancers think and gave me a lasting appreciation for their art and its many communities of practice. I held my own against people who had fifty, sometimes eighty pounds on me, and so gained a level of self-confidence that I’d never experienced before. Most importantly, it was a critical outlet during what, for anyone, is a very difficult and confusing period of life.

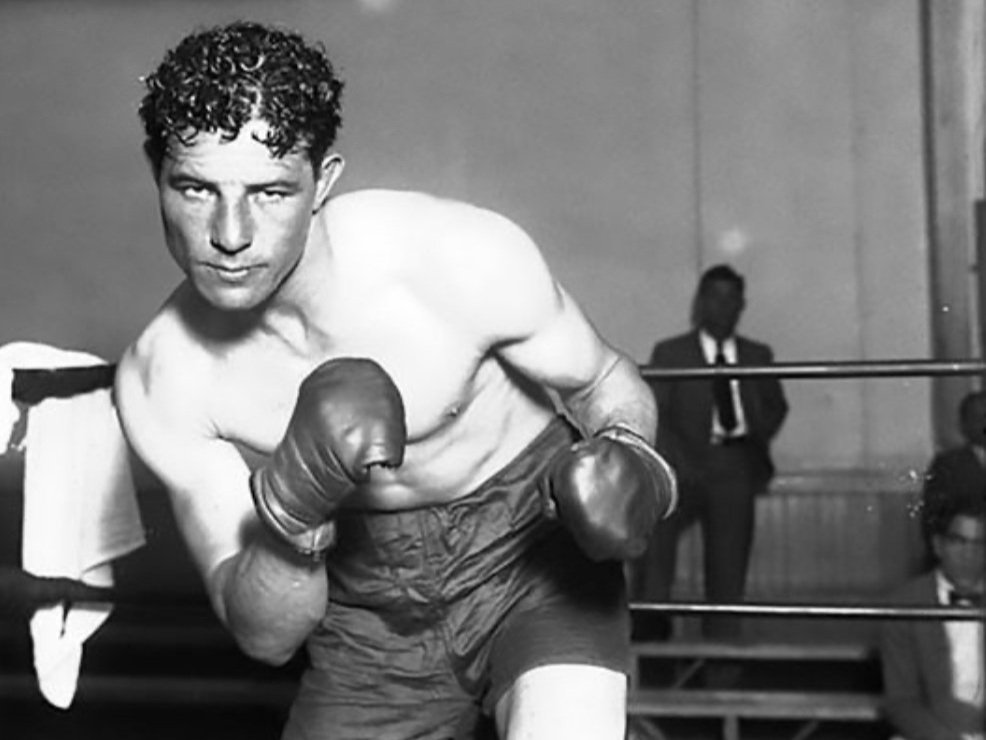

In combat sports, a feint is a move intended to deceive or distract an opponent.

Here’s Max Baer doing his darndest, circa 1940. (source)

My dedication to Muay Thai tapered off midway through college, and I eventually supplanted it with trail running. It was a necessary switch and something that provided me with an even more powerful, albeit solitary, outlet. Even so, it was not long before I started to miss all of the things that my prior training had given me. I imagined a future in which I ran to keep my conditioning up but re-dedicated myself to Muay Thai, went at it even more ardently, maybe even competed in something more official than my previous ghost fights.

A revivalist's fervor soon overtook me. I ordered the best gear I could—Fairtex shin guards, Twins boxing gloves, and bona fide Thai boxing shorts with an inseam that would make even a cross-country coach blush. Then, I bought a monthly membership with a local MMA club and threw myself back into training almost every day for hours at a time, convinced that I was well on my way to realizing that imagined future.

Call it wishful thinking or hubris—either way, I tend to jump into things too quickly, and this was no exception. I kept at it for a few months but ultimately came away with bruised ribs, battered pride, and a few hundred dollars sunk into a misguided attempt to reclaim that younger version of myself. Embarrassed and still a little sore, I let my membership run out and quietly withdrew from the sport again.

This was six years ago. I told myself that I would find a way to sell the gear and recoup some of those sunk costs, but never really made the effort. Then, I convinced myself that it hadn’t been the right time for me to start practicing again, and that when the time did finally come along I’d have everything I’d need to pick up where I left off. That never happened, either. Instead, the gear stayed tucked away in the furthest corner of my closet and traveled with me through three moves.

Now, my wife and I were set to move again, and we would be downsizing from a townhouse to an apartment in the process. We needed to clear out as much junk as possible, so I couldn’t put off dealing with that gear anymore.

I had two options, so far as I could see: I could either take the gear to the used sporting goods store, or I could see if a local Muay Thai gym would accept them as a donation. It was no sooner than I had conceived of the second option that a new imagined future burst forth like a touch-me-not flinging its seeds.

I’d pay it forward! Give another earnest young neophyte with unmarked shins the chance to gain what Muay Thai had given me! Spare a local gym the expense of replacing equipment during such lean and uncertain times! It would be a befitting end to that gear bag’s long journey, and a boon to suit my fancy.

There was a hitch in that sanguine but hastily conceived plan, however. It was a Sunday, so none of the local Muay Thai gyms were open, and I needed to be rid of the gear yesterday because we were moving in less than a week, and finding a suitable home for it was an admittedly frivolous thing compared to all the rest that needed to be done in order to vacate our current home and settle in at our new one. There was really only one option, then.

I drove to the used sporting goods store, walked in and approached the counter, then showed the man behind the register what I had to offer.

“What’re ya lookin’ t’get out of it?” he asked while inspecting one of the shin guards. He said it so quickly that I could’ve sworn he’d asked “Ya lookin’ to get out?”

Well, I was getting out of the sport, wasn’t I? That much should have been obvious. In fact, I had been getting out for a long time, but had never fully admitted it—not with any sense of finality, at least.

All of this occurred to me at the same time that I realized what he had actually asked. I almost mumbled an affirmative before correcting myself and telling him that I’d take whatever I could get for them.

“Alright, twenty dollars then,” he said.

And that was that. I accepted his offer, no questions asked. I didn’t even consider the fact that it was a paycheck’s worth of gear I’d just given away for pennies on the dollar. Instead, I stuffed the twenty-dollar bill in my wallet and walked back to my car.

I sat in the car for a while, twirling the key lanyard around my finger. I could have refused the offer. I could have waited a day before going to see which of the local gyms would accept the gear. But really, there hadn’t been a choice—or, rather, I hadn’t left myself one. If donating the gear had really mattered that much to me, I would have planned for it way sooner. I wouldn’t have left it to the last minute. And in leaving it to the last minute, I had foregone the solution that would have most suited my fancy.

It had all been a feint, of course. I didn’t need the money, necessarily. And I didn’t even really need the space. What I needed all along was just to be rid of the gear—that, and permission to put the period of life that it represented behind me.

The cold matter-of-fact-ness of the transaction was discomfiting and so brute simple as to feel a little insulting. But it was also freeing, because it allowed me to see how, in clinging to that gear, I had chosen days long past and gilded with imagined futures over a fully inhabited present. In so doing, I had denied myself a trove of gifts far in excess of what those gilded days had given me—and therein lay the real opportunity cost.

There’s a closet full of similar quandaries that I’ll get to one day, hopefully, each as discomfiting and painful and necessary as this one had been. But I understand the difference between sunk costs and lost opportunities now, and won’t need much more schooling beyond that. The only thing left to do, then, is to keep practicing.

This piece was written by Chris Robey, who also writes as tumbleintheroar. You can find more of his work here.